Many active investors try to maximise their investments in the stock market by attempting what is known as “timing the market” in an effort to identify the best time to enter and exit. But does timing the market work?

This question is relevant because timing the stock market is not an indifferent strategy. If it doesn’t work, it means investors who rely on it have to live with the pain of its failure. And this pain includes the opportunity cost of not using another strategy such as lump sum investing or dollar-cost averaging.

In this article, we will consider if timing the stock market works and if it’s a good strategy for investing in the stock market. We’ll cover:

- What is market timing?

- Does timing the market work?

- Eight reasons market timing invites pain

- Alternatives to timing the stock market

[Are you looking for the best way to invest your money, grow wealth, and achieve your financial goals? Learn more about how Sarwa can help with stock marketing investing by scheduling a fee call with a Sarwa Wealth Advisor.]

1. What is market timing?

Market timing is an approach to investing where investors wait for the best time to enter or exit the stock market in an attempt to maximise their returns.

Investors who engage in market timing don’t enter the market when they have money to invest. Rather, they keep the money as cash until they believe it’s the right time to enter the market.

The right time to enter the market, according to this approach, is the end of a bear market or the beginning of a bull market. When an investor buys at this time, they can maximise their returns since they have bought at the lowest price possible.

Similarly, the right time to exit the market is at the highest peak of a bull market or just at the beginning of a bear market. By selling at this point, returns can be maximised.

2. Does timing the market work?

Since market timing is not the only investment approach out there, asking the question “does timing the market work” must involve a comparison with other strategies.

One strategy that has been used to assess the efficacy of market timing is passive investing. This strategy often involves systematically investing in index funds or ETFs that track the performance of a market index, without regards to timing. That is, while the market timer wants to buy and sell at the right time, the passive investor doesn’t try and attempt this guessing game, instead relying on the long-term success of an overall index.

So, how does market timing compare against passive investing?

In a ground-breaking study published in 1975, William Sharpe, a Nobel Laureate, showed that investors timing the stock market must be correct 74% of the time to beat a passive index fund with the same risk profile.

Years later, Morningstar reached a similar conclusion – active investors have to be correct 70% of the time in order to gain an edge over passive funds, which is practically impossible over the long run.

So what about today? Have market timers been able to rise to the challenge of outperforming passive index funds of ETFs?

The short answer is no.

And the best way to show this is to consider mutual funds that use this market timing strategy and compare them with their market indices. Why? While we can justify the inability of individual investors to time the market successfully, it is harder to justify professionals who have the education, knowledge, and experience to do it if they continue to fail. Moreover, it is the main objective of these mutual funds to outperform market indices, a job investors pay them for.

So, how do they perform?

Research by Morningstar showed that only 23% of active funds outperformed their passive funds rivals between 2010 and 2019. Also, the research shows that the longer the period in view, the lower the chances of active mutual funds to outperform their indices.

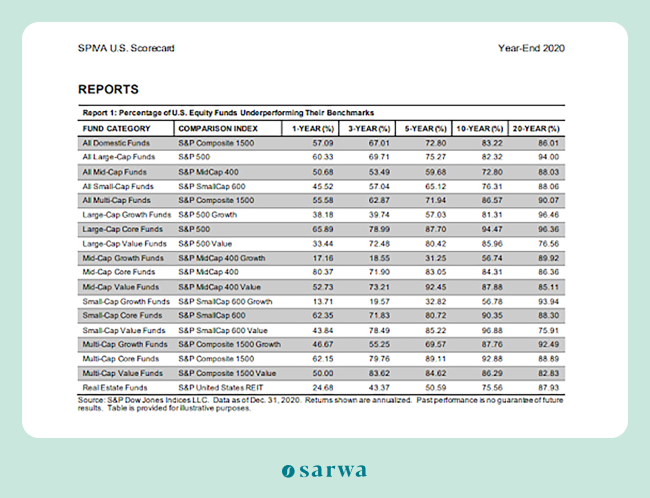

An 2020 SPIVA report published by S&P Global showed that more than 57.09% of active US equity funds underperformed the S&P Composite 1500 index in 2020. Over three years (2017-2020), 67.01% of them underperformed, 72.80 over five years, 83.22% over 10 years (2010-2020), and 86.01% over 20 years. Again, the longer the period, the more market timing fails to deliver.

2020 SPIVA Report

Even Warren Buffett placed a bet in 2007 that a passively managed fund would outperform a collection of hedge funds managed by Protege Partners over the next 10 years. In 2017, the S&P 500 Index fund had returned 7.1% while the hedge funds returned an average of 2.2%.

If all these professional fund managers find it difficult to make market timing work in any consistent fashion (especially over the long term), what then is the fate of the average retail investor who does not have the time, knowledge, education, experience, and funds that these fund managers have?

However, it bears repeating that the failure of market timing is not painless. Now, we will consider eight reasons why market timing invites pain.

3. Eight reasons market timing invites pain

1. The risk of missing best-performing days

When investors who time the market make wrong decisions, it can be very hurtful to their bottom line. For example, the market timer might risk being out of the market in the best days/weeks/months to be in the market.

A study by Merrill Edge, an investment firm, highlighted this in a vivid way. If an investor stays invested in the S&P 500 Index between 2009 and 2018, their $1,000 at the beginning of the period would be worth $3,530 at the end of the period.

However, suppose that the investor is a market timer and their market timing led them to be outside of the market in the best-performing 10 months of that time period. In that case, their $1,000 would only be worth $1,580. If they were out for the best-performing 20 months, it would be worth just $958.

A similar study by Dalbar, an investment research firm, showed that an investor who stayed in the market from 1995 to 2014 would have earned a 9.85% annualised return. However, if the same investor missed just the best-performing 10 days during that period, they would have only earned a 5.1% annualised return.

In essence, those who stay in the market never have to risk missing out on the best-performing days of the market, while those who time the market may end up being left on the sidelines during rapid (and ultimately unpredictable) uptrends.

2. Missing out on compound returns

Similarly, investors who time the market often miss out on the compounding returns that staying in the market provides.

Compounding occurs when money invested in the market earns interest and that interest also earns new interest, ad infinitum.

By refusing to enter the market and holding on to cash until the “appropriate” time, market timers can miss out on the benefits of compounding. Worse still, the idle funds can lose value if the economy is in an inflationary period.

3. Buying when the dip goes lower

You perhaps have heard the popular mantra “buying the dip.” This involves market timers waiting for a stock to hit rock bottom before buying it.

However, no one really knows when the market is at the absolute rock bottom. Many market timers end up discovering that what they thought was the lowest point was just the beginning of a bear market. They end up losing more and more money as the dip keeps going lower.

This loss would be even more painful if the market timer did not participate in the bullish run of the same stock but had to endure the bearish run due to market timing.

As Callie Cox, senior investment strategist with Ally Invest puts it, “Buy the dip is one of those things that works really well on paper, but it doesn’t work well in real life.”

4. Emotional investing instead of strategic investing

Timing the stock market means an investor is constantly watching stock tickers and usually becomes very emotionally invested in the short-term volatility of the market. The problem here is that those who are emotionally attached to short-term volatility are often subject to the fear and greed cycle that Warren Buffet considers the bane of successful investing.

Fueled by emotion, the market timer can make costly mistakes that lead to buying when the dip is just beginning to go lower, or selling when the bullish run is just about to intensify.

The downside here is that such investors cannot embrace an investment strategy like the Systematic Investment Plan. Instead, they are always tossed here and there by what market news headlines dictates. As a result, it’s harder to pursue a strategic long-term plan that will help them achieve their financial goals.

5. Higher costs

Investors who time the market might have to execute more transactions than those who follow a strategy and prefer spending time in the market than timing it. More transactions means more cost (except for the market timer uses a trading platform like Sarwa Trade that offers commission free trades).

Investors in mutual funds also have to pay higher management fees (in the form of expense ratios) compared to investors in passive index funds or ETFs. Yet, these higher fees do not often translate to better returns than passive funds, as we have seen. In fact, the report from Dalbar quoted above shows that many mutual funds with expense ratios exceeding 1% often underperform their indices by up to 3%.

6. Higher risk

Those investors who attempt to time and outperform the market are taking up an additional risk compared to passive investors who track the performance of an index.

Taking more risk is not bad in itself as long as there is more returns to compensate for the risk. However, as we have seen, the expected higher returns hardly materialise.

7. Wasting time and energy

For retail investors, attempting to time the market is a time-consuming and stressful endeavour. This often involves a lot of technical analysis in an attempt to find support and resistance.

But why spend so much time and energy on an endeavour that is costlier and not more profitable than investing in a passive index fund or ETF?

8. Failing to benefit from bear markets

For those investors who choose to stay in the market for the long haul, even bear markets can be profitable.

How so?

There are opportunities to buy more shares at the same price and to reduce the average cost of investing in a stock.

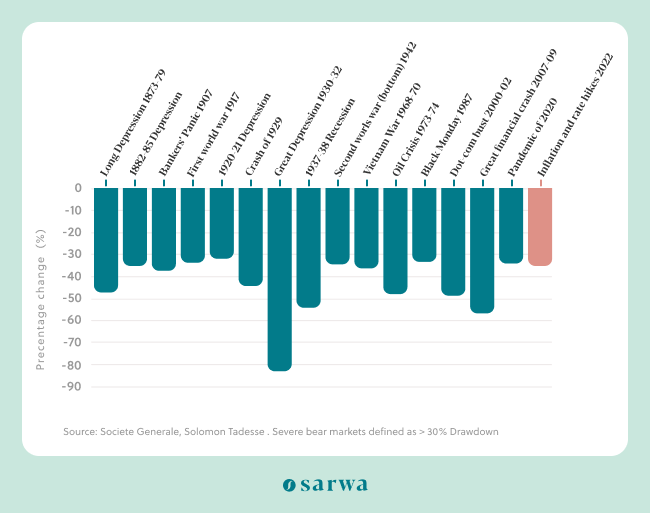

This is important since bear markets (and even recessions) will be inevitable several times throughout our lifetime. The graph below shows how different recessions have impacted the US economy over the years. For example, during the Great Depression, there was more than a 80% drop in the stock market.

Some market timers would have sold their shares out of panic during these periods, losing money in the process. However, the long-term investor would have benefitted from these bearish runs and recessions (see below), stayed the course, and then further benefited from the bullish reversals.

How do long-term investors benefit in bear markets or recessions?

Suppose Investor A invested $1,000 in Stock A in January at $100 per share, giving him 10 shares of the stock. If that stock falls to $80 per share in February, Investor A can now buy 12.5 shares and the average cost of his investment in Stock A will now be $88.8/share ($2,000/22.5 shares).

If the stock falls to $50 per share in March, Investor A can now buy 20 shares with the same $1,000 and the average cost of his investment will now be 70.59/share ($3,000/42.5 shares).

In essence, even a bear market can be beneficial to the investor who remains in the market. By the time the market comes to a bullish run, that’s more opportunity to earn compound returns and increase gains.

The market timer cannot enjoy such benefits. He/She sees the bear market as an absolute enemy.

4. Alternatives to timing the stock market

So does timing the market work? Not really.

Are there any good alternatives? Yes, there are at least two.

Lump-sum investing

With a lump-sum investing strategy, you enter into the market at any period you have specified, irrespective of the amount you have to invest or the condition of the market.

If Investor A has decided to invest 20% of his salary on the last day of every month, irrespective of the state of the market, he is a lump-sum investor. If Investor B got a $10,000 income from a one-off job and put it all in the market on the day she earned it, she is a lump-sum investor.

Because the lump-sum investor enters the market fully at a single point irrespective of market conditions, they are able to derive maximum benefits from compounding.

A study of the markets between 1926 and 2019 by Vanguard has shown that with a 60/40 stock-bond portfolio, lump-sum investing outperformed dollar-cost averaging 67% of the time over 6 months and 92% of the time over a year.

Dollar-cost averaging

Some investors who are not confident enough to enter the market at once can choose to spread out their investments over a defined period of time. For example, Investor A can decide to spread his/her monthly investment over 4 weeks while Investor B above can spread the $10,000 income from a one-off job over the next 5 months.

This approach is called dollar-cost averaging (DCA). New investors who are afraid of entering the market all at once often prefer it. It is also profitable in a bear market where investors can get more shares at the same price and reduce the average cost of investing in a stock.

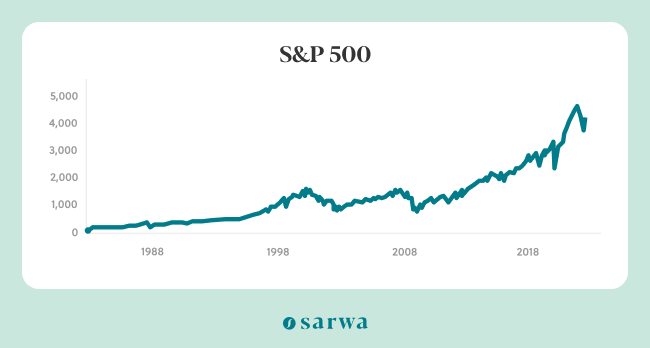

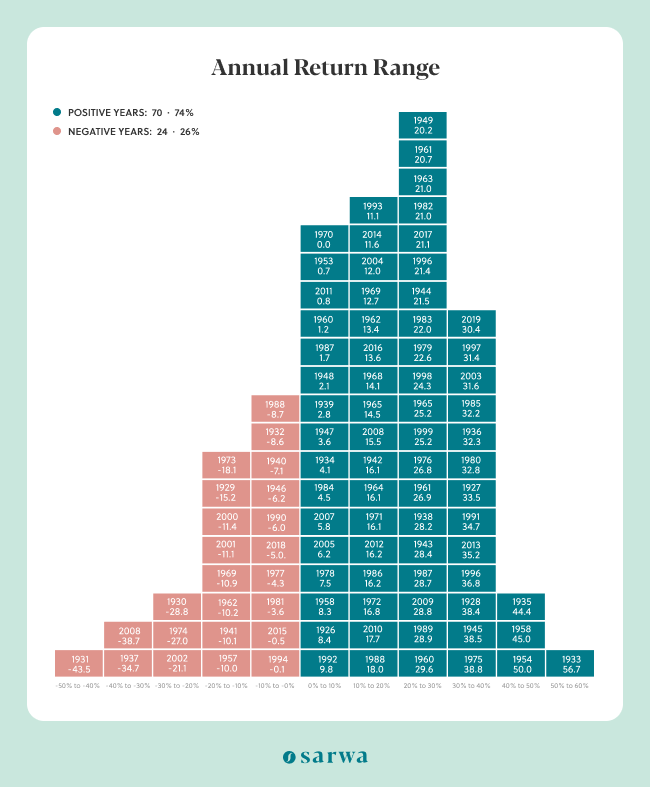

However, because the market rises more than it falls (as shown in the graph below), lump-sum investing is often more profitable, especially over the long term.

Overcoming market timing with lump-sum investing or DCA

Instead of timing the market, passive investors can use either a lump-sum or DCA approach to invest in a diversified portfolio of index funds or ETFs that has been created by a digital wealth advisor.

With Sarwa Invest, we use the Nobel-prize winning Modern Portfolio Theory to create diversified portfolios of ETFs that take into account your risk tolerance, time horizon, financial goals, and current financial situation.

Though market timing and active investing go together, they don’t have to be mutually inclusive. An active investor can ditch market timing and embrace lump-sum or DCA investing as well. The only big difference with a passive investor is that the active investor creates their own portfolio instead of using one already created by a digital wealth advisor.

If you are an active investor, with Sarwa Trade, you can buy your own stocks and ETFs and create your own portfolio at zero commission and zero local transfer fee. You can also enjoy fractional trading, SSL security, market reports, and the absence of any minimum account balance requirement.

[Are you tired of the pains caused by market timing and looking to embrace a better investment approach? Learn more about how Sarwa can help you or schedule a free call with a Sarwa wealth advisor to get started.]

Takeaways

- Market timing is the attempt to wait for the best time to enter and exit the market to maximise returns.

- Though market timing is popular, it doesn’t work well for retail or professional investors.

- Market timing can also cause pain to investors. This includes missing out on compound returns, missing out on the best days/weeks/months in the market, higher cost, and higher risk, among others.

- Lump-sum investing and DCA are better investing approaches that do not involve timing the market.